Photo by Robert Altman

< STORIES, ARTICLES, & RECOLLECTION

Berkeley's Own Don Quixote

by Diana Stephens

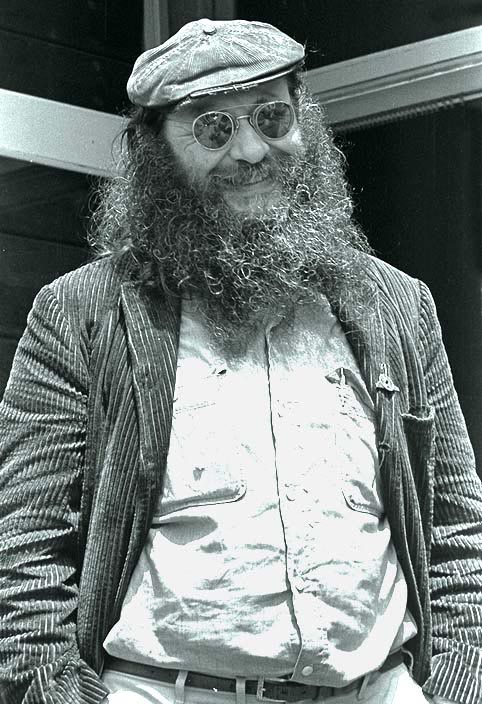

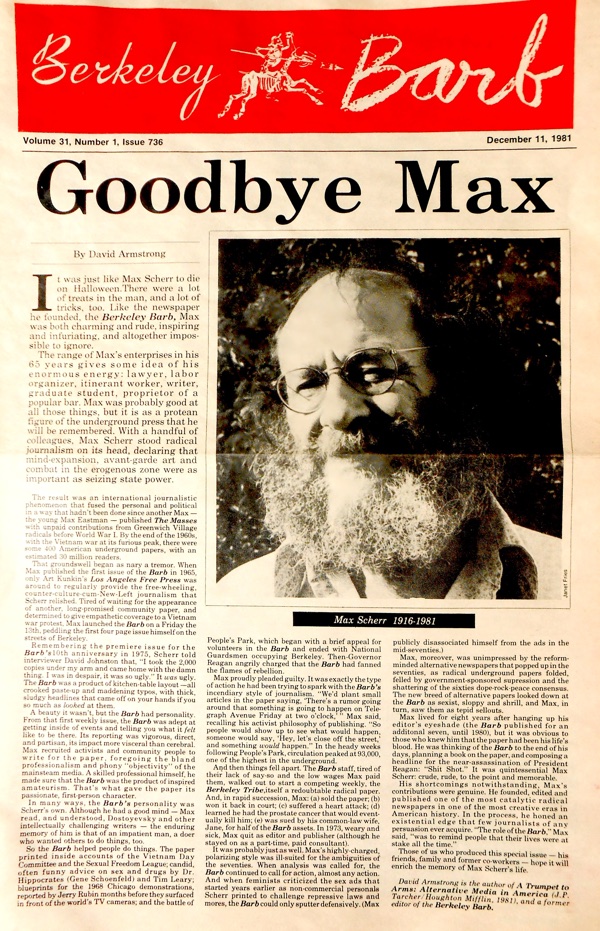

You can learn a lot about a person from his obituaries and I’ve found a dozen of them for Max Scherr, the publisher of the Berkeley Barb, the west coast’s most popular underground newspaper of the 1960’s and 70’s. In fact, Rolling Stone magazine, in its January 1982 edition, ran a full-page eulogy entitled “The Death of a Founding Father.” The biographies comment on Max’s Leftist sympathies, his support of Berkeley’s protest movements, and how he survived obscenity charges, a labor revolt, a nasty palimony lawsuit, and over a decade with cancer. The consistent theme is that Max was a very controversial person. People loved him, hated him, and felt conflicted about him. In the very last edition of the Barb, resurrected by staffers in Max’s honor, David Armstrong described Max as “both charming and rude, inspiring and infuriating, and altogether impossible to ignore.” [i] Max’s life, and those of his family, friends, and fellow revolutionaries offer an intimate portrait of Berkeley’s radical elite. Max’s belief in a free press contributed to the revolutionary zeal that infected the entire city by advocating for individual freedoms and civil rights for all people, protesting against the Vietnam War, police brutality, government spying, economic inequality, environmental concerns, and for the decriminalization of drugs and prostitution. Max Scherr and his Berkeley Barb staffers were true American revolutionaries, and way ahead of their time.

My own interest in the Barb stemmed from the fact that I had first seen it when I moved to the Bay Area in 1974 at the age of fifteen. At that time the Barb was primarily considered a pornographic paper, and as a teen I was an avid reader when I could get my hands on it. I remembered this a few years ago while doing research at the Berkeley Main Library and thought to ask to look at some old copies. When I opened the first bound volume, which was published in 1965, there wasn’t anything even remotely risqué about the content. To the contrary, it was clearly a Leftist political newspaper dedicated to an anti-war and pro-civil rights agenda. Yet, five short years later T&A dominated the pages. I needed to know why this had happened.

In June of 2010, I interviewed Max’s oldest daughter Raquel, who is the unofficially designated family historian. [ii] We met at her home in north Berkeley, a quaint cottage nestled among several others that she had shared with her late husband Marc Blanchard. She inherited her father’s bound copies of the Barb and several boxes of his personal papers, as well as his passion for Leftist politics. Raquel’s relationship with her father was, however, complicated. Max left his wife Estella and their three children after an affair with a younger woman named Jane Peters came to its logical conclusion when she became pregnant with Max’s child. Jane’s pregnancy devastated Raquel, her mother, and her brothers, and the ramifications exist to this day. So, while she defends her father ferociously against many of his detractors, she harbors her own very personal resentments.

There are certain facts about Max’s life that are generally agreed upon, and Raquel elaborated on them. Originally from Baltimore and trained as a lawyer, Max was forced out of town by “goons” after trying to organize taxi drivers. He rode the rails to California and then headed south into Mexico because he was told things cost less there, revealing one of his most controversial personality traits, that of being famously tight-fisted. There he met his future wife Estella, a medical student who later had to leave school when it was discovered she was married and pregnant. Horrified by the anti-Semitism unleashed in Europe, Max volunteered for the U.S. Army and, despite poor eyesight and a history of tuberculosis, served by following the troops into Normandy while Estella and their young family waited the war out in Florida. When Max was discharged, he relocated his family to the Bay Area, finally settling in Berkeley as a law student working at the Bancroft Library. He lost that job after he took offense when asked to sign the university’s mandatory loyalty oath. He lost another at the Bancroft Whitney Publishing House in San Francisco when he connected land laws to segregation policies in his research. So, Max turned to entrepreneurship and opened a beer and wine bar called The Steppenwolf serving the bohemian crowd in Berkeley. In 1965, Max used the proceeds from the sale of The Steppenwolf to launch the Berkeley Barb.

Max designed the Barb’s banner as a skeletal Don Quixote on horseback brandishing a Campanile-tipped lance; this was a reflection of himself as a man on a mission to right the wrongs of society, and he intended to prick the consciences of all those around him. As he wrote in the very first issue of the Barb on Friday, August the 13th, “If we do our job well, we hope even to nettle that amorphous but thickhided (sic) establishment that so often nettles us.”[iii] The Berkeley Barb became a popular alternative source of news and information as Max and his small staff of young writers covered the civil rights, labor rights, and anti-war protests far differently than the traditional press. His commitment to Leftist politics was well established, although certain ethical questions arose from time to time when Max’s belief in freedom of speech and press delivered unexpected (and to many, unwelcomed) consequences. Max was not prepared when the freedom of expression he longed for later evolved into sexist content in his paper, which in turn created as yet unforeseen conflicts over the profits.

A modest 8-page fold over, the first Berkley Barb was launched by a dozen or so people, led by Max, to bring attention to local activist movements. These radical writers included Marvin Garson who was on the Free Speech Movement’s steering committee as it endeavored to raise bail money for defendants. Staff writer Bob Randolph reported on the troop train protests in Oakland with a rather more sympathetic perspective than that of the San Francisco Chronicle or Oakland Tribune journalists. George Kaufman, aka Sgt. Pepper, bemoaned the recent demise of a local reader-owned paper called the Citizen. Telegraph Avenue merchants made up the bulk of the Barb’s early advertisers, and hawkers sold it on Berkeley’s street corners for 10 cents. John Jekabson, an early editor of the Barb, filmed a protest rally at Sproul Plaza in May 1966, and there is Max Scherr working his way through the crowd with a stack of his papers tucked under his arm.

I sought out other people who had known Max and that led to an interview with Judy Gumbo Albert, one of the founding members of the Yippies, who worked for the Barb selling the well-known classified ads, often referred to as “personals.” [iv] Judy was a student at Cal at the time, and much younger than Max so she viewed him as a smart and interesting old Jewish grandfather type. She freely acknowledges that Max could make a person feel special, as Judy felt when he agreed to print one of her essays about the new women’s movement, where she was free to declare that as feminists, “We will fight against our oppressors, regardless of their class, race or sex.”[v] Yet, she also referred to Max as a “total son of a bitch” because he entitled that article, “Why the Women are Revolting.” Judy was left to seethe while Max reveled in his double-entendre. The fact remains, however, that Max gave a voice to women when few others would.

The interview with Judy was of particular interest because she spoke directly to the issues facing the women involved with movement “heavies,” those who were influential within the movement. Her boyfriend and husband to be, Stew Albert was a revolutionary alongside Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman. Judy joined a women’s consciousness-raising group that included Jane Scherr (common-law wife of Max,) Anne Weills (wife of Robert Scheer,) Diane Lipton (wife of Lenny,) and the poet Alta. These college-educated women were often ignored, given menial tasks, and only learned leadership skills by observing their media hungry partners. Judy admitted that the women felt “unequal in our relationships . . . that the men were out there doing it, and we were expected to be servants in some sense to the men.” [vi] By continually confronting the men in their personal lives, these women fought the daily battles that led to the national women’s liberation movement, and by developing an “action faction” within their group, they applied movement methods to promote a women’s agenda. In early 1969, Stew wrote (and Max published,) “I am a Male Cracker” in the Barb and equated women with oppressed minorities by stating, “I am a . . . chauvinist sitting inside his plantation dreams of superiority.” [vii] Despite the obvious tensions between these men and women, they found ways to live and work together that promoted a more egalitarian society for all.

Max and the other editors at the Barb covered stories and promoted alternative viewpoints that other news sources refused to offer. Gar Smith became Max’s peace beat reporter after participating in the Port Chicago vigil and standing trial in the San Francisco District Court. Gar wasn’t paid for his reporting, but his political messages were published weekly for months and that was worth a lot to this young idealist. Gar described Max as scruffy and earnest, sweet and gentle, a “genial provocateur.” He fondly remembers Max moving briskly down Telegraph Ave., quick to stop and engage with anyone who wanted to converse. Yet, Gar also admitted to being clearly agitated after reading an exposé on Max’s financial success (largely due to the sex ads) in the late sixties, saying, “We were risking our lives and Max has all this money and we’re not even being paid.” [viii] These financial and feminist issues soon led a majority of the staff to walk out, strike, and then start their own paper, the Berkeley Tribe. Max’s financial success and unwillingness to pay his staff seems both contrary to Max’s own sympathies with regard to labor rights, and completely consistent with his reputation as a tightwad. His own daughters have felt the need to address their father’s “lunatic relation to money” as well as his inability to “bridge the gap between his ideology . . . and what later mushroomed into sexist advertising.”[ix] Those who knew Max don’t believe he meant for his politically progressive paper to morph into a revolutionary weekly dominated by sex ads, but that is what the free press came to look like within its pages. The Berkeley Barb was one of the first public outlets for suppressed urges among many people to express both their revolutionary political views and newly unleashed sexual appetites.

It’s true that Max lived a very simple lifestyle and eschewed materialism, but he had an uncanny way of squirreling away money. John Jekabson worked for Max both early on in 1965 and ’66, and then again in ’68 after a stint with the Peace Corps. While John was an editor at the Barb and was paid accordingly, he described how Max paid writers 50 cents an inch and made deductions for fractions of an inch. [x] John assumed that because Max carried his cash around in a shoebox that he couldn’t have much, and it never occurred to him that Max was putting money into personal bank accounts. However, the New York Times reported that by 1975, Max had contracted to give $250,000 to a trust that would support him for the rest of his life, although it is assumed by most who were concerned, that his tax attorney, Harry Margolis, may be the only one who knew where the money actually went, and Margolis took that secret to his grave. [xi]

John also described a side of Max that others had only lightly touched upon. As mentioned earlier, around the time that Max sold The Steppenwolf and started publishing the Barb, he met a young woman, Jane Peters, and entered into an affair. Ultimately, Max left his wife Estella and their children, though never divorced, to start a new life and family with Jane. When asked about Max and Jane, John (who like most people at the Barb were unaware of Estella and the children) described them as enjoying their social status as Berkeley’s “first couple of the underground,” but also mentioned their different personalities. [xii] Jane was shy and mild-mannered while Max had a large ego and a quick temper, their ages accentuating the differences. To illustrate how this played out publically, John related how for several years Max had hosted a weekly dinner at his house after each week’s paper was sent off to the printer. The staff would enjoy an evening off while Jane cooked for everyone and Max held court. One of those evenings Max had a special guest, the folksinger Phil Ochs who was enjoying a bit of celebrity at the time. Making a special effort, Jane prepared an artichoke soufflé, which flopped and was a disappointment for all, but for Max was an embarrassment in front of a notable guest. He yelled at her, calling her horrible names and swearing at her in front of everyone, making them all very uncomfortable. So while Max could be a charming, genial host, he also exhibited a certain disregard and disrespect for his new, young partner, as well as their guests.

It is difficult to get a truly clear picture of Max as there is very little primary source information directly from him. He wrote nothing of himself that survives aside from love letters to Estella. He gave few interviews, and those he did grant dealt with his legal woes. In the mid seventies, Jane sued Max in one of California’s very first palimony lawsuits pitting feminist lawyers Doris Bryn Walker and Faye Stender against one another in an acrimonious court room drama that was featured in mainstream publications such as the New York Times, where it was observed that, “the controversy provide[s] insight into the lifestyles of an important element of Berkeley’s radical society in the last decade.” [xiii] When Max and Jane separated, there were no reliable laws in place to resolve the financial impacts of the dissolution of a union that was not official. [xiv] Jane’s case collapsed when Estella testified to being Max’s legal wife, while Max took advantage of this legal fact to avoid paying Jane any additional alimony or child support. While Estella wouldn’t voluntarily grant Max a divorce, no one is exactly sure he asked for one either. Also, Jane (who to this day goes by the surname Scherr) is constantly referred to as Max’s second wife despite the lack of legal documentation, and of course, it was their divorce that caused such a divisive ruckus among Berkeley’s radicals.

Raquel is particularly defensive when the topic of Max’s lawsuit with Jane comes up in conversation. Clearly biased, Raquel didn’t feel Jane should get any money aside from child support as she was never married to Max, and was especially angry about how some feminists used Jane and Max’s relationship to establish legal precedents benefitting common law families. Estella, perhaps because she was an immigrant with limited language skills, was ignored by the feminists in Berkeley. Raquel was forced to advocate for her mother against them, and felt it was rather ironic that these feminist lawyers were fighting over the profits derived from sex ads that they expressly hated. In fact, when the feminist paper Plexus refused to print her response to an article in the September 1975 issue supporting Jane’s lawsuit, Raquel self-published a four-page pamphlet entitled, “Plexus Perplexus,” to argue her points. Frankly, there was no need to worry about Jane or Estella receiving any money. In the end, the only people who benefitted from the profits made at the Barb were attorneys, and to some degree, Max himself, although his modest lifestyle quickly dispels any notion that he took full advantage of it.

Berkeley in the 1960’s and 70’s was a revolutionary time and place, impacting virtually every aspect of our lives today. The Berkeley Barb addressed all the issues that concerned the activist movements of that era. The Barb may have started out primarily addressing free speech, civil rights and the war in Vietnam, but it soon gave attention to a host of other political and societal concerns. There were cover stories on economic inequality, police brutality, sexual freedom and birth control, feminism, gay rights, government surveillance, decriminalizing drug use and prostitution, environmentalism, holistic health practices, fair labor practices, and prison system reform, among many other progressive ideas. Historian Gordon S. Wood considers the measure of radicalism to be the amount of social change that takes place, and credits a free press with shaping public opinion. [xv] By that measure Max and his contemporaries were clearly radicalized as they attempted to fundamentally change our governmental and societal norms. Today, same sex marriage is legal and recreational marijuana is not far behind. Today, a committed socialist can be a viable candidate for the presidency, as can women. Today, the Internet provides a worldwide platform for a variety of opinions, giving writers unprecedented access to public forums. The country’s radicals have accomplished a lot in the last fifty years.

Max Scherr was a colorful character at a fulcrum of yet another American Revolution. Max was full of contradictions, yet he was consistent in his need to right the wrongs he found. From the Baltimore taxi drivers, and Europe’s Holocaust victims, to believing black lives matter, and women are of greater consequence than even he imagined, Max believed in people. Of course, there were many others trying to define the new moralities of that age, but Max did tilt his lance toward the windmills more visibly than most. So while his friends and acquaintances compliment him on his Leftist leanings and commitment to freedom of speech, some also criticize his reputation as a “capitalist bloodsucker,” and would question the exploitation of women in his paper. Often as not, these contradictory comments come from the same person.

[i] David Armstrong, “Goodbye Max,” Berkeley Barb, December 11, 1981, 1.

[ii] Raquel Scherr, interviewed by author, Berkeley, CA, June 8, 2010.

[iii] Max Scherr, editorial, Berkeley Barb, August 13, 1965, 4.

[iv] Judy Gumbo Albert, interviewed by author, Berkeley, CA, December 20, 2010.

[v] Judy Gumbo, “Why the Women are Revolting,” Berkeley Barb, May 16, 1969.

[vi] Gumbo Albert interview.

[vii] Stew Albert, “I Was a Male Cracker,” Berkeley Barb, January 31, 1969.

[viii] Gar Smith, interviewed by the author, Berkeley, CA, May 28, 2010.

No hard copy of this exposé, which appeared in theBerkeley Fascist (later known as the Berkeley People’s Paper and published by Allan Coult,) has been found, but it is referred to in Arthur Seeger’s The Berkeley Barb: Social Control of an Underground Newsroom (New York: Irvington Publishers, Inc., 1983) and various other sources.

[ix] Apollinaire Scherr, email to Gar Smith, August 5, 2015, and Maura Dolan, “Max Scherr,” quotes Raquel Scherr in Max’s obituary, San Francisco Examiner, November 2, 1981.

[x] John Jekabson, interviewed by author, Oakland, CA, December 30, 2010.

[xi] Gar Smith, “Sour Notes From the Underground,” New West, January 1, 1979.

[xii] John Jekabson, email to the author, January 1, 2011.

[xiii] Wallace Turner, “California Court Fight Involves Control of the Berkeley Barb,” New York Times, August 7, 1975.

[xiv] Stephanie Coontz, Marriage, a History: From Obedience to Intimacy or How Love Conquered Marriage (New York: Viking Penquin, 2005), 279.

[xv] Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York: Vintage Books, 1993)

• All interviews collected by the author were videotaped and are available in the CSUEB library